Interviewsand Articles

A Lost Mariposa Garden

A Lost Mariposa Garden

by Richard Whittaker, Apr 2, 2006

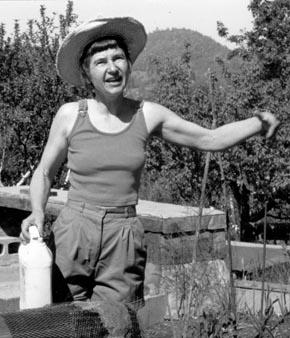

Jacqueline Airamé at work in her garden in Mariposa, CA (date unknown)

Coming home late one evening, I found a message on my voice mail. I didn’t know Jan Peters, but next morning I returned her call. "I'm eighty, she told me, and an artist." Jan wanted me to know about a unique garden in the little town of Mariposa not far from Yosemite - about a three-hour drive from the Bay Area.

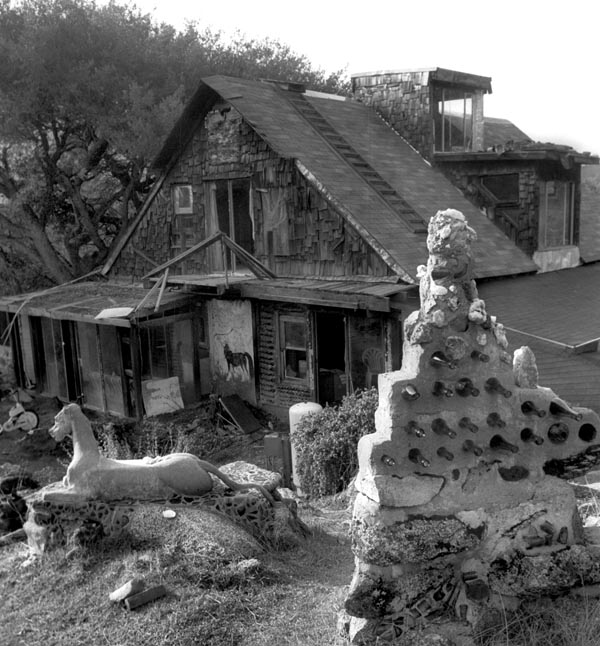

It was being bulldozed. "Soon, nothing will be left," she said with strong emotion. "Could you go up there and see what's left? It's just a terrible shame it's disappearing with hardly anyone knowing about it!" Her friend, Jackie Airamé, had built the garden over a period of thirty-five years, she told me.

The more I heard, the more intrigued I became.

Two friends of Airamé still lived in the area, Jan explained. “They can show you the place. You can call them. Jackie's garden is a treasure and it will be gone without a trace!"

I called them.

Ann Mendershausen answered.

The developers had given the Mendershausens one week to salvage whatever was left of the Airamé garden.

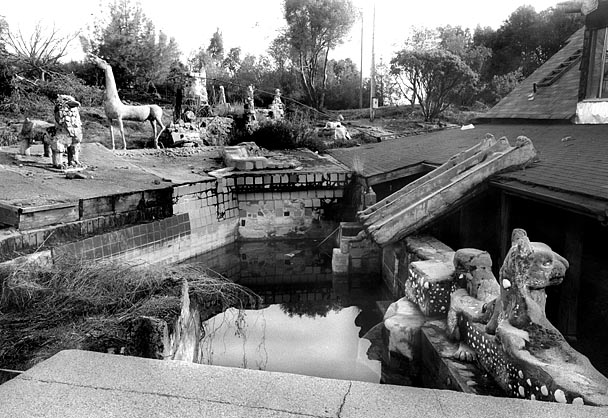

Ann and her husband hoped some of the pieces could be placed in Mariposa as public art. But the larger pieces—a griffin, a couple of horses and two large cats, among others—were too heavy to move without special equipment. They weren’t sure they’d be able to manage it, “and the blue mosaic hillside has already been bulldozed,” Ann told me.

A blue mosaic hillside? I'd heard enough.

Two days later, on a cold, wet February morning, I was on my way to Mariposa. As I drove east on Hwy. 580 gray skies gave way to patches of blue. The hills of Altamont Pass had already turned green and further east, a tentative green carpet was appearng under the bare almond orchards along highway 132.

A few miles east of Merced, a sign—“Fruit Basket”—caught my eye and I pulled over to stretch my legs and get a snack. A long line of rusted old farm equipment bordered a large parking area.

Stepping through the door, I found myself in a spacious, utilitarian room that was virtually empty. "Where's the fruit?" I asked a middle-aged woman sitting behind a counter.

“This time of year, there’s not much,” she said.

Right. Then I spotted the little array of plastic bags spread out across a lone tabletop. Dried fruit and nuts. Getting past my reaction, it felt as if I'd stumbled through a loophole into another world.

The woman at the counter was keeping to herself. Whatever I made of it all was my business apparently. And now I was curious. Noticing a door at the back of the empty salesroom, I walked over and peeked through its window. My goodness! I was peering into a large warehouse full of… and only then did the other words on the sign sink in. "Fruit Basket and Ag Museum."

I turned and looked at the woman. “Can I go in there?” I asked.

She nodded.

Pushing my luck, I asked, “Can I take a few pictures?”

She nodded again.

The mysterious garden in Mariposa was calling me, but I couldn't resist exploring this unexpected trove of antique home appliances, gasoline tractors and eccentric relics. It was as odd a collection of bygone equipment and humble gadgets that anyone could hope to find. And I had the entire place to myself.

I wandered down one aisle and up the other.

Leaning up against an old glass jar I noticed a small sign: “Please help pay for the light and heat for the museum." Another card revealed that everything was from the personal collection of one Charles Parish. Close by, next to a broom jig, sat an antiquated cabinet with a vintage ceramic bowl on top. Inside it a few dollar bills were visible. I paused, reached in my pocket and dropped another dollar bill in.

On the way out, a bag of pistachios in hand, I pulled back onto the highway. As the miles passed by, I found myself thinking about the 'Ag Museum' and Mr. Charles Parish. My gosh, all the work involved! And a pang of remorse crept into my awareness.

Why hadn't I left more for this stranger's labor of love? Mr. Parish had invested so much to leave a record of a world he knew was quickly vanishing - the work of a single person hoping to make a difference.

It was an honorable impulse - this wish to preserve pieces of a way of life hoping that something of its essence could speak to those who came after it was gone. Wasn't something like that why I was publishing the magazine? And what about this garden I was about to visit?

"You have to see it," Jan had said to me. She meant that I'd see what it had cost its maker. I'd see its beauty. Perhaps I'd even see why objects crafted from the heart were as important in life as the food we eat. Wasn't Mr. Charles Parish moved by something like that, too? "Here are the tractors and tools and household gadgets we used. We made a life from the earth for ourselves, and for others."

It was painful seeing how I'd left one stingy dollar. How much of life is like that? But it was too late to go back and become that better person I wished I could be. I needed to get to Mariposa while there was still daylight.

MARIPOSA

The Mendershausens’ place was well off the beaten path. When I finally found my way to their house, Ann met me. We’d been standing outside talking for several minutes when I spotted a man coming towards us from the woods. It was Ann’s husband Ralph. As we shook hands, I was a little alarmed. From the scratches on his face, it looked like he might have been dragged through a long stretch of underbrush. But his grip was firm and he seemed in good spirits. “Give me a little time to clean up,” he said, disappearing into the house.

“He’s got to wash the poison oak off,” Ann said in a matter-of-fact tone. Standing there, it was easy to see that maintaining a little mountain retreat took some work. It probably contributed to the bond among this group of friends who all knew Airamé’s garden.

Twenty minutes later Ralph reappeared, a new man. We all walked down to their studio. As I was looking at Ann’s ceramic work, I heard something like the sound of a howling animal coming through the walls. “It’s a kid on one of those quad-bikes!” Ralph said. “Their parents just let them run wild. There’s not much you can do about it.”

Even up here there was a culture clash, he explained. “We used to be able to see the stars at night. Now it’s getting suburban out here. But if you gave me the choice, I’d rather be surrounded by rednecks than suburbanites any day. At least they feel some connection to the land.”

Ralph Mendershausen had gotten his PhD in German History, but with the difficulties associated with finding a job in the university system, had decided he’d rather build a house in the Sierras and teach high school. Now, after twenty-one years, he’d retired. Ann had been a ceramic artist going way back, and Ralph had been drawn to sculpture himself. Their first house had burned to the ground in a forest fire, but they’d rebuilt. What I found when I arrived on their property was something of an artists’ retreat. Besides the new house and studio, there was a guesthouse and a couple of other out buildings. Sculptures and whimsical constructions were scattered across the grounds. I was in the company of Airamé’s kindred spirits. The way Jan Peters had talked earlier about Airamé and her garden and—as my experience with the Mendershausens continued to unfold—my sense grew that whoever the mysterious garden maker was, something set her apart.

Airamé had been close to Jean Varda, I was told. I recalled Henry Miller’s essay, “Varda: The Master Builder” (Remember to Remember, New Directions 1941). Of Varda, Miller wrote, “No wonder people love to visit his place. I've never met a man so plagued with visitors. They come like locusts, people from all walks of life.... They come in search of that mysterious elixir which no vitamin seems able to supply our people with: the joy of creation.”

“Jackie had married a Frenchman and their place was very unusual,” Ann explained. She also told me that Airamé had worked on another project for years, one that never came to fruition. “Wait a minute,” she said and disappeared into the house.

She came back with a twelve-page brochure, Magic Kingdoms—A Search for Bewitching Environments. It was a preview of a book Airamé had envisioned. In its preface, Airamé wrote, "I used to ask people everywhere I went if there were any really strange creations around— houses built out of bottles or junk or shells. Any castles? Glass tree houses? People’s fairy-tale-like recollections were enough in themselves to keep me fascinated—rumors of underground fruit orchards, mountains carved in eagles and gods, ‘mistletoe heads,’ an old lady who lived in a redwood stump. 'Would I like to see the place where white clay pours out of the mountain? Six thousand sculptures in one garage?' But these were no rumors. They were all true."

Her search, she wrote, was inspired by the French book Les Inspires et Leurs Demeures [The Inspired Ones and Their Dwellings] by Gilles Ehrmann, Paris 1962. In her preface, Airamé continued, “Ever since seeing this spell-casting book I've been haunted more and more by a torrent of visions and intangible longings. In hope of exorcising these chimera, I took to going on trips to search out American counterparts to the European inspired ones.”

Goodness. By now, I had no doubt I'd made the right decision in driving up, and I realized the daylight hours were fast disappearing. “Maybe we better head over to the garden,” I said, and we all got into the Mendershausen's Subaru. On the way over, I heard more about Airamé and the good times they'd shared together.

Looking Back

Two months have passed since my visit to the Airamé property that afternoon. Pondering what to write, I’m reminded of something Richard Berger said to me a few years back. Reflecting about his life as an artist he said, “I find myself questioning what seems to be a pretty arcane cul-de-sac within which I find myself. In a moment of transient bitterness, I described it to myself as squandering my imagination working in this corner making things that virtually nobody sees.”

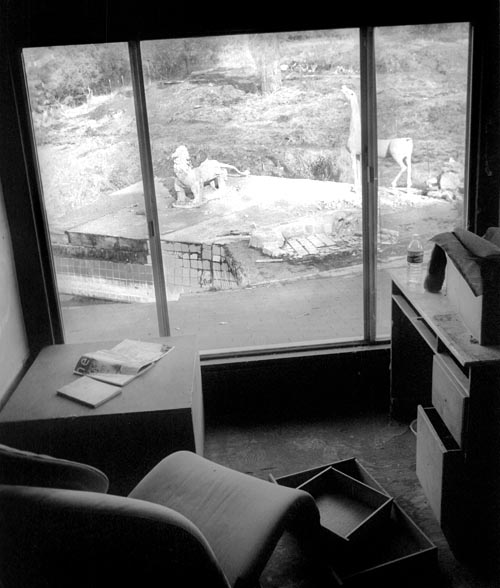

Airamé's garden is like that. As Henry Miller wrote of Jean Varda, “The joy of creation was there. It was truly there." It's what I felt that afternoon looking through the broken remains of the garden. And I felt at home.

Airamé’s garden, what was left of it, reminded me of parts of my own life—of people I’d known and places I’d lived - of the taste of possibilities that life offers if only one can stop and turn towards the moment. For instance, there was the day I gave in to an impulse and opened a little can of blue enamel paint. With careful strokes a quotation from T.S. Elliot appeared around the edge the clawfoot bathtub in my little student apartment. This minor act of transgression released a startling amount of joyful energy.

The destruction of Airamé’s art garden was not complete. And what remained, now spoke in a minor key of what must have been a joyful feast. What is the joy of creation if not a taste of sudden freedom? Look at the cat rolling on its back. But all is not roses. The empty torso of the horse lying near the entrance to the property is like a fragment left over from an epic tragedy.

And what about the horse with its neck stretched out? Is it in joy or suffering? Either way, what do these abandoned artifacts express if not the words I found in Airamé’s own brochure, “I have been haunted more and more by a torrent of visions and intangible longings.”

My visit to Airame's Mariposa garden took place thanks to her friends. As for the garden maker herself, I was to understand that she was not available for a visit. Perhaps one day she might tell me some stories, but I would have to wait to see.

Yet, something cried out for a witness. Even in ruins, here was something original - genuine. Could it be told? All this I felt, and therefore was called back to myself. What is original, I was reminded, returns one to one's self, to a place where the deep questions are still alive - the opposite of closing a book.

Postscript: The Mendershausens and friends succeeded in rescuing most of the large pieces from Airamé’s garden. I don't know where they are today.

About the Author

Richard Whittaker is the founding editor of works & conversations and West Coast editor of Parabola magazine.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

TO OUR MONTHLY NEWSLETTER

Share Your Comments and Reflections on this Conversation:

On Apr 4, 2023 Nola Maury wrote:

My own attempts to create a garden with a few sculptures of my own pale in comparison, but the feelings of joy in making my creations and gardens are identical to Airames.On Apr 4, 2023 Cosima wrote:

so beautiful.On Apr 3, 2023 Elizabeth Andrew wrote:

How utterly beguiling & charming.....I'm now on a hunt to look for "inspired Ones & Their Dwellings" around Europe. We have a house on the island of Crete, where there are several quirky finds one stumbles across. One being a bar/taverna in the town of Kalyves , the Koumos Taverna story is that a Greek husband began building something for his wife and never stopped. full of curios.On Apr 3, 2023 Sharon Lovejoy wrote:

But I WANT to know where they are today?? And why this garden was destroyed? What is the gardener/creator's story. So many unanswered questions about a rare work of art. More?On Apr 3, 2023 Mimi Pantelides wrote:

Lucky man to have been in the Airame garden. Not surprising that others wanted to destroy it. Unfettered joy is so often crushed. I disagree about the horse however, I don’t think the horse is screaming. The perfect authenticity of the figure is real horse being horse. The artist understood the horse essence without the photographic details. I wish I could have gone there then, though I’ll imagine it and enjoy the essence - Mariposa perfume.On Apr 3, 2023 Linda wrote:

What is original returns one to one's self....wow...beautiful article...imspiring...as a fellow artist I feel this deeply...each random unexpected act of creation does indeed unleash a wave of energy! An exhilaration of liberation from the restrained self...On Apr 3, 2023 River wrote:

This inspiring picture of original whimsy created and shared is a joyful example of a life inspired which is possible for all who choose.On Apr 3, 2023 Denisse wrote:

Touches the deepest part of me. The impulse to create, the healing power of the process to authentic expression and the medicine it serves for as long as it lives. The creative collections of my private art gallery for one makes more sense now from your sharing. Thank you.On Apr 3, 2023 Linda wrote:

We must cherish what honors spirit…wherever we find it…wherever. Especially these days.On Jan 15, 2015 Julia wrote:

Thanks for this great tale of artistic adventure.